Reading the Land

This section written by Marit Parker.

Planning a permaculture design requires that we learn to “read the land.” Reading the land takes time. And that’s good, because if you’re planning a major change, you don’t want to rush into it and then realise you’ve changed your mind or made a mistake.

Different seasons bring opportunities for different observations, so in summer you may notice some places where plant growth is lush, and others where it’s drier and plants take measures to conserve water. In winter, frost and frozen water can reveal different patterns and hints about what lies underneath. Sun and shade are of course important factors, and taking time means you can observe the plot when the sun is at its highest and lowest points in the sky, at opposite ends of the yearly cycle, and all the points in between.

What is growing in different areas also gives clues to attributes such as where water is flowing through the land, and where the soil is fertile. Get to know the weeds in your plot and find out what they can tell you about the soil, the availability of water, and the microclimate.

Seeing all the creatures that live in your plot can be harder, as many stay hidden. However, you may spot tracks, poo, webs or shells, for example. What different habitats are there and where? What does this tell you about the site?

Don’t forget to look at your plot in its context with neighbouring areas. If you have a slope, what happens above and below it? Where does water come from and go to?

Look at its historical context. What has happened here before? What changes have been made in the past? This could include changes due to human activity, such as buildings erected or pulled down, paths or roads made, trees planted or felled. Or it could be changes due to physical factors such as fire, erosion, flooding or drought.

Seeing places in their historical context can bring a different perspective to our observations, the long view. We may start to appreciate different aspects in terms of their relative permanence. This may help us consider our own efforts differently, in terms of their own relative permanence.

It may become apparent that, for example, a damp depression probably used to be a pond that has filled in over time. How does this change how you see the land?

As your understanding of your plot deepens, start considering what effect changes might have. What might happen if you change where water goes? How will it affect your neighbours? How will it affect plants and animals living near the water now?

As you become more aware of all the different forms of life passing through or living in or near your plot, all of whom will be affected in different ways by your plans, it can become difficult to know what to do for the best.

Are the projects you want to do going to enhance the land, or will it cost too much in terms of disrupting, or even destroying, existing niches and habitat?

Many of these potential upsets can be offset working by hand instead of using machines. Working by hand means it is possible to introduce changes gradually, allowing time for more learning about and reading the land as you work, allowing time for those affected by the changes to adapt, and also allowing some flexibility if you realise your plans could benefit from some changes.

Major changes to plans, once they have been started, are more difficult, so it is worth taking time not only to read the land but also to mull over the work you want to do, the effort it will take, the effects it may have.

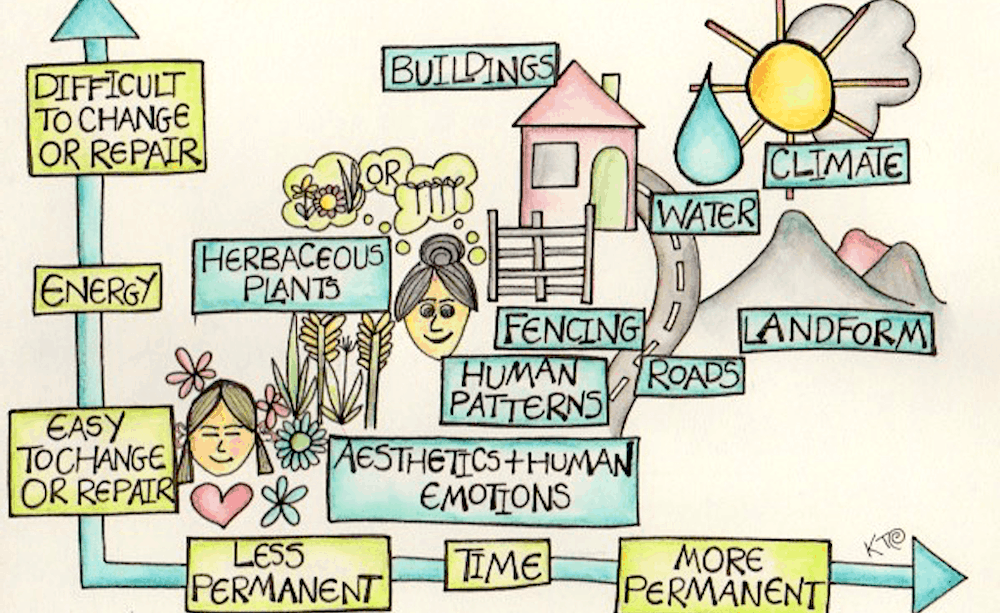

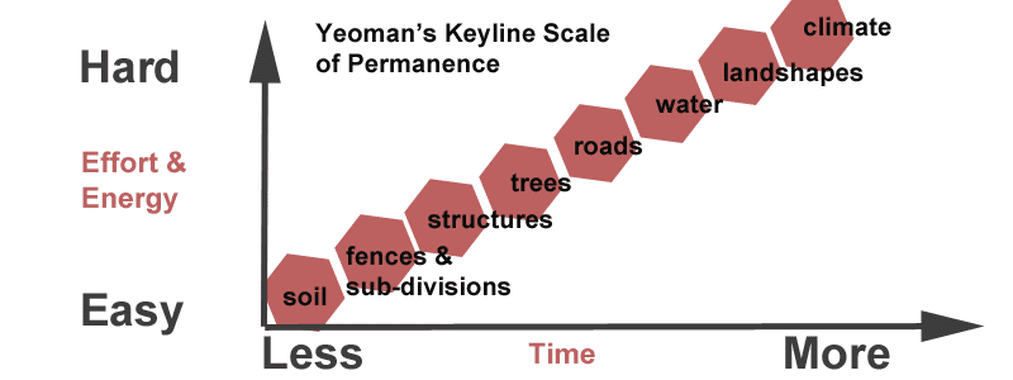

The scale of permanence is a tool you can use to gather information, analyze opportunities, and prioritize components that will have the biggest impact for the least effort. It is also a tool to measure the potential for error, and to avoid making huge ones. As you can see, landform is hard to change and repair, and soil is super easy to ruin (and repair), and most of your landscape changes will affect both, so think hard before you start digging!

Here’s a thorough, if slightly meandering, video explanation of SOP and how it connects to making changes to your landscape, from Richard Perkins

When you make changes to the landscape, do you consider how long those changes will last, and/or what the long-term impact of those changes will be? Also, when you plan your timeline for implementing your design ideas, it becomes clear that some tasks (repair damaged soil) will take much longer to accomplish than others (plant strawberries)…and by the same token: some mistakes (strawberries planted in the wrong spot) will only take a few minutes to remedy, while others (adding toxins to soil) will take many years to correct.

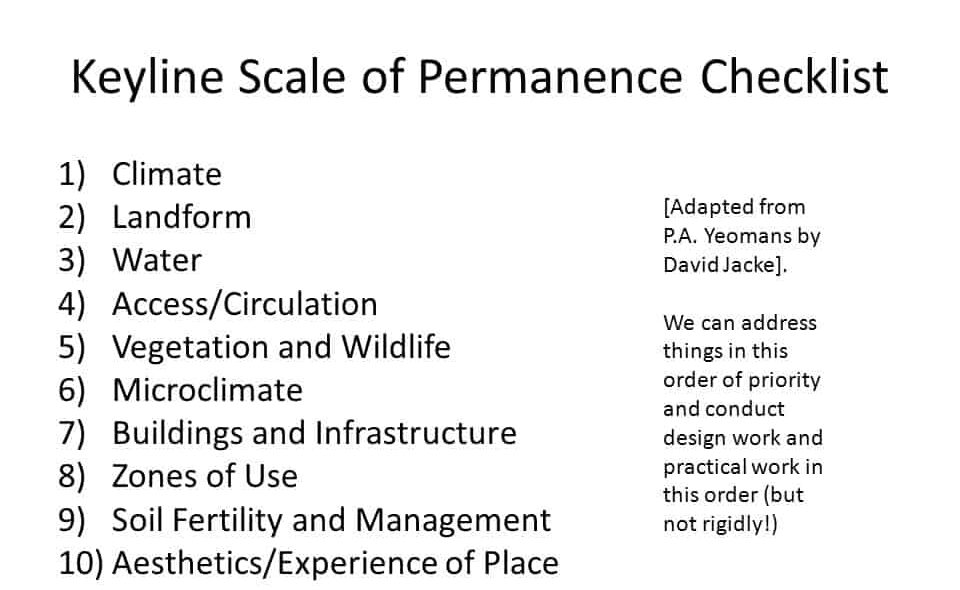

As such, when we use something called a “Scale of Permanence” to organize our thoughts and actions, we can avoid big mistakes and create a workable, conscious timeline for our design project. There are a few versions of the Scale of Permanence since P.A. Yeoman, but he was the first to frame it as such. His understanding of a site’s hydrology left an impact on the world and is important for permaculture designers to understand.

The idea is that you rank components from easiest to change or influence (and thus easiest to correct if you make a misguided design decision) to hardest to change (once you’ve changed the climate, for example, it will take a huge effort to change it back), and then observe and analyze the site with those rankings in mind. The SOP gives us a way to organize our observations, and to envision the potential impacts of any changes we’d like to make. Try creating a set of questions and observations that follow this pattern.

Want to learn more about this and other topics related to permaculture, sustainability, and whole-systems design? We offer a range of FREE (donations optional) online courses!

Relevant Links and Resources

Here’s a lovely article on Reading the Land. It’s part of an excellent series from Native American Seed.

Planning for Permanence with Yeomans’ Keyline Scale.

This article from Permaculture Research Institute gives a great history and overview of the Scale of Permanence and why it’s such an essential part of the permaculture toolkit.