Paradise gardening as a political imperative

Before i delve into Permaculture Food Forest, I’d like to share this essay, which completely changed my life, in 1999, and set me on the path I’m still on today, Joe Hollis writes:

“Our world is being destroyed, in the final analysis, by an extremely misguided notion of what constitutes a successful human life. Materialism is running rampant and WILL CONSUME EVERYTHING, because its hunger will never be sated by its consumption. Human life has become a cancer on the planet, gobbling up all the flows of matter and energy, poisoning with our waste. What can stop this monster?

Nothing. Just this: walk away from it. It is time, indeed time is running out, to abandon the entire edifice of civilization / the State / the Economy and walk (don’t run!) to a better place: home, to Paradise.”

Permaculture Food Forest: How do we get to Paradise?

Easy! We grow it, everywhere we go.

At this point, we don’t need to dwell on why growing permaculture food forests and paradise gardens is so important. If you’ve made it to this place, you know why. And it’s not a hobby or even a choice anymore.

At this point, devoting massive portions of your spare time to gardening is an imperative. So, let’s get to how to create a diverse, thriving garden that will last for a thousand generations and provide sustainable yields over multiple layers of time, space, and function.

Permaculture Food Forest: Guilds, Companion Plants, and Polycultures

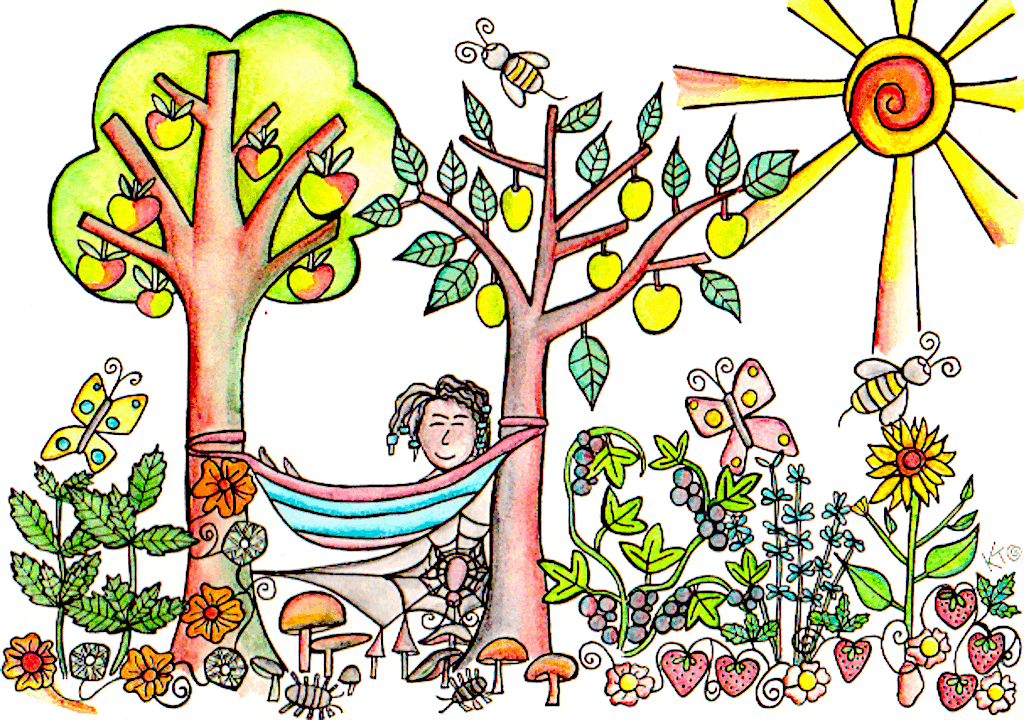

Permaculture is known for long-lasting, low-maintenance perennial gardens that stack plants in time, space, and function. The polar opposite of a monoculture, a well-planned polyculture will yield year-round, providing food, seeds, and compost crops for people, wildlife, and microorganisms alike.

Because they are so diverse, polycultures yield more and are less susceptible to disease and insect infestation.

The result of this type of agriculture is a lush, abundant oasis, teeming with fresh fruit and birdsong, and when I heard Joe Hollis call this type of agriculture “paradise gardening,” it made sense to me and I started calling it that, too.

Everything you need to know about gardening, or quite possibly everything you need to know about life. You can learn from the plants.

Every time you interact with a plant, whether it’s a microscopic one or a giant ancient tree, you learn something about the planet, you learn something about yourself, and you learn something about how to bridge the gap between what we currently call humanity and the potential for a sustainable future as a coexisting symbiotic species here on the planet in the global biosphere.

As gardeners with our hands in the soil, we have the opportunity to create a legacy that we can see immediate results from our own lives, and we can see reverberations as we move through the garden over the seasons and over the years.

Gardening gives us immediate feedback. The plants are able to exhibit evolutionary traits very quickly, because their life cycles turn over so much more quickly than ours.

So, we can learn from them about how changes in the biosphere, changes in microclimate, and even tiny changes in the way the wind blows can have profound effects on the success or failure of an organism and the community that organism is connected to.

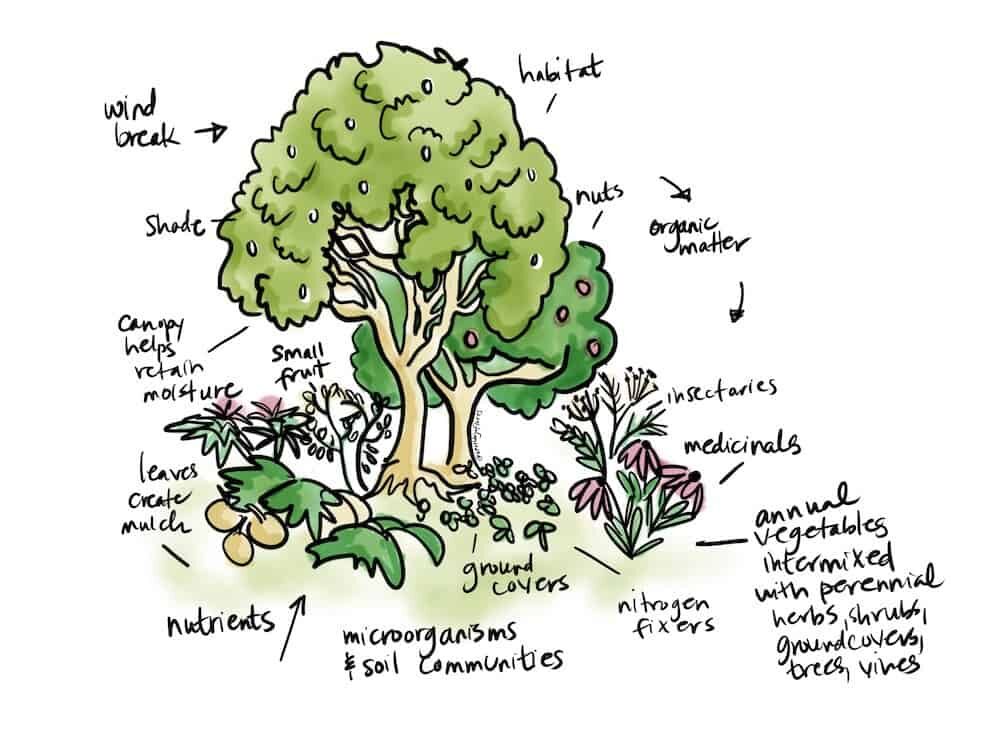

We can use the natural forest as a model for building guilds that layer functional niches within niches in space and time. When we plant several of these guilds together the result is a multifunctional, polycultural garden that thrives in low-maintenance perpetuity.

To understand this, think of the way a forest looks: small plants and debris cover the ground so that no soil is bare. Larger plants and shrubs grow up against small trees, and tall trees fill in the gaps to create an overstory canopy that is rich in bird and animal life.

Vines wrap around the trees and drip across the skyline. Something is always sprouting while neighboring plants die or go dormant for the season, and some kind of food is always available.

The entire permaculture food forest remains moist and cool even on hot days, yet cold winds and killing frost rarely penetrate the dense growth, so the interior of the forest remains temperate, while sun loving plants crowd the edges where there is more light.

Every nook and niche has something to offer and is home to something or someone, so that every square foot reeks of life and diversity.

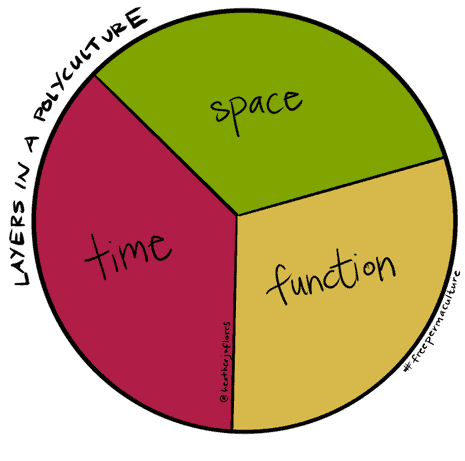

We can view the layers of a polyculture in three parts: function, space, and time.

Permaculture Food Forest: Layers in function, space, and time

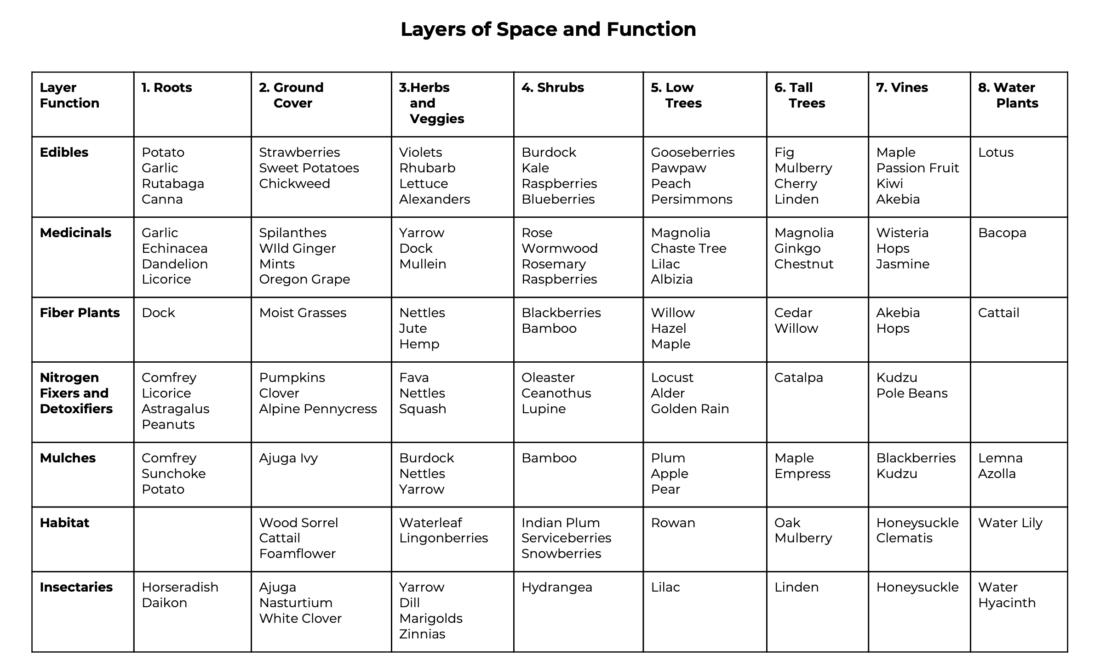

Here’s a rundown of niches the plants in your garden could occupy, to create layers of function, space, and time:

Layers of Function

- Edibles. Most edibles also serve other functions, and indeed, you will find that there is much crossover among all of these layers. Plants like to stack functions, and so should we. Most annual vegetables are easy enough to grow; also try perennial edibles such as fruits and berries.

- Medicinals and aromatics. It is quite possible to grow and process all or most of our medicine with just a few carefully selected plants. We can grow remedies for colds, headaches, muscle pain, toothache, allergies, and stress, as well as fill our homes with wonderful smells!

- Ornamentals. There is no such thing as a plant that is strictly ornamental. Every plant fills a function other than just being beautiful. It may, for instance, create shade, wildlife habitat, and forage opportunities.

Still, don’t be afraid to choose to grow something simply because you think it is beautiful. Some gardeners become obsessed with “practical” function and forget to include beauty and inspiration as essential components. Don’t let it happen to you! - Fiber plants. Fiber plants add functional diversity to the garden, as well as providing opportunities for money-making craft projects. Some fiber plants, such as bamboo, can provide stakes and trellis materials, while others are better for making baskets and sun hats.

- Nitrogen Fixers and Detoxifiers. Your garden should have a few areas in cover crops at all times to ensure that we give back what you take from the soil. You should also include, in each garden guild, at least one nitrogen fixer.

- Mulch plants/bioaccumulators. There are many perennial plants that accumulate large amounts of leaf mass, which can then be harvested as mulch for neighboring plants.

Include several of these in your overall garden design, but because they grow so big and so fast, give them plenty of room so they don’t overwhelm smaller plants. Comfrey is the go-to plant for this niche. It is easy to grow from just a small root cutting, it can be cut down several times a year for mulch or compost, and it will grow back within a few weeks. - Habitat plants. In the interests of giving back to nature and nurturing species other than our own, I encourage you to include a healthy dose of habitat plants in your permaculture food forest design.

Habitat plants provide shelter and forage for wildlife and are often best placed in the outer edges of a garden, where they can delay and nourish any hungry critters who might otherwise eat your primary crops.

It is also a good idea to create habitat within the garden: places for songbirds to nest, and places for snakes and toads to hide before they come out to eat slugs at night. The more lush and diverse your garden grows, the more it will become a natural ecosystem of its own, with you, the gardener, as just one of the many living species within. - Insectaries. Many gardeners have an inclination to eliminate every insect from the garden. However, if we strive instead to encourage a healthy and diverse insect population, the insects will mediate one another, and the garden as a whole will benefit.

Many plants attract or repel some sort of insect, which means you can choose which insects to encourage or discourage in your garden. Insectary plants could be plants that attract beneficial insects, plants that repel harmful insects, and/or plants that attract pollinators.

Layers in Space

- Tall Trees. Tall trees are the slowest growing and longest living layer, with some species living up to five thousand years. Be sure to plan for their size at maturity; grow herbs and vegetables in the space the trees will later fill.

Tall trees provide wildlife habitat, lumber, erosion control, food, medicine, firewood, and windbreaks and create the essential canopy that helps shade and mulch the forest/garden floor. - Small Trees. Here we find many of our large fruits, some of the nuts, and plants that supply countless other products, such as shade, mulch materials, wood, and wildlife habitat.

Small tree crops are the heartbeat of permanent agriculture, and every garden should have at least one, if not several. Most small trees take several years to fruit but will usually outlive the gardener who planted them, providing food for many generations to come. - Herbs and Vegetables. Many plants in this layer need partial to full sun, so design plenty of sunny edges around the garden to accommodate them. Most herbs are perennial and can live twenty years or more, but most veggies are annual or biennial, taking up space in the garden for only a short time.

This makes them an excellent choice for planting next to perennial plants that are still young and small. The annuals will shade the ground and provide food for you but will die by the time the perennial needs the elbow room. - Shrubs. Trees and shrubs require less maintenance than annual vegetables, and some can produce hundreds of pounds of food each year, with almost no labor once they get established. Most will benefit from regular mulching and pruning.

Many of the fiber plants fall into this category, as do most small fruits and berries. Establish shrubs when the trees are still young, because many of them need sun to get established.

Once established, most shrubs will be relatively drought and shade tolerant and will help filter the wind through the low parts of the garden. This is important because though trees provide an excellent windbreak, if there are no shrubs, then the open space creates a cold wind tunnel, which can be rough on tender herbs and vegetables. - Vines. Vines add a jungle-like feel to the garden and help maximize vertical space, which is especially good for cramped urban settings.

The long stems can be used for basketry. If left un-trellised, some vines will make a good ground cover. Or use the trellis to create a microclimate by placing it to reflect sun, block wind, or both.

You can prune back vines every year or let them climb wild, toward the sun. Most vines are shade-tolerant but will flower and fruit toward the top, where they can reach the light. Vine brambles make great habitat for spiders and other beneficial insects.

Many nitrogen-fixing legumes are climbers, which makes them good choices for the vine layer. - Ground Covers. Ground covers provide a living mulch over soil that, if exposed, would dry out or cover itself with weeds. It is good to get ground covers established when the taller plants are still young and the sunlight still reaches the ground.

Once established, most ground covers will spread readily and can be extended to other areas of the garden. It is quite possible, and highly recommended, to establish a semi-permanent ground cover over most of the perennial garden. - Roots. All plants exist in the root layer, but some are grown primarily for their fleshy, edible roots and tubers. Some have shallow roots, while others penetrate twenty feet or more into the soil.

As a general rule, assume there is at least as much growth below the soil as you can see above ground. Try to space your plantings so that roots don’t compete for elbow room but instead stack together as they grow down like the layers of branches and foliage above. - Water Plants. If you have water features, you’ll need water plants to cleanse and aerate the water and provide shade, food, and habitat for fish, waterfowl, and humans. Water plantings could even occupy seven MORE layers, under the surface!

Layers in Time

Sure, summer is the peak season for most gardeners, but in many climates you can have food and flowers year-round, and you can also design plantings to succeed each other, over the many years to come. Use niches in time, combined with niches in space and function, to deepen and diversify the productivity of your garden.

Tips for using the time layer:

- Choose plants that you’ll harvest at many different times of the year. For example, most nut and fruit trees yield in the autumn, when summer vegetables have finished, and brassicas (broccoli, kale, and their like) and salad greens grow well in the off-season, when deciduous leaves have fallen and summer shade gives way to cool winter sun.

- Plant annual flowers and veggies in the spaces between young trees and perennials.“Undersow” cover crops into the soil between almost-finished existing crops, to avoid that period of bare soil (and lost time) between plantings.

- Include plants that will perpetuate themselves by either dropping seeds in the garden or spreading underground, and include their future offspring in your long-term vision.

- Extend the growing season for tender vegetables by using greenhouses and cold frames to protect plants from frost.

Want some examples? Here’s an article with a few specific examples of successful garden guilds that work in a lot of different climates.

P.S. Diverse doesn’t mean crowded!!

Always be sure to give each plant plenty of room to grow. Clotted areas provide the moist, sticky conditions many harmful pests need to thrive, and when plants are too crowded they compete for nutrients, which weakens them and makes them vulnerable to insects and disease. So water, weed, mulch, and prune when necessary. The most common mistake gardeners make is planting things too close together— remember how big the plants will be at maturity, and make sure they have the space they need.

Most plants, from annual daisies to ancient yew trees, generally follow the same life cycle: the seed grows into a plant which flowers then produces a fruit which contains seed.Each stage provides us with an opportunity for a yield, or in other words, we can use plants at different stages. Imagined the life cycle of plants as a flow of water, with each different way of using plants creating eddies in the flow.

Check out the example chart here, and then download this blank PDF version to try for yourself.

Want to learn more about this and other topics related to permaculture, sustainability, and whole-systems design?

We offer a range of FREE (donations optional) online courses!

Relevant Links and Resources about Permaculture Food Forest

If you’re working in a temperate zone, Maddy Harland’s series on permaculture food forests will be of great value to you. Even in other climates, the core principles will still apply.

Start with this video:

Joe Hollis discusses his approach to Paradise Gardening.

Be sure to subscribe and check out the rest of his channel. It’s wonderful!

Graham Bell, author of the Permaculture Garden, gives a tour of his permaculture food forest.

If you’re of a more tropical persuasion, check out Sarah Wu’s permaculture food forest in Costa Rica.

And here’s something for cold climate folks, from Kareen Erbe.