For the most part, this website focuses on providing resources for folks who probably don’t have the resources to own (or even rent) more than an acre (or less) of land. We see this as an important niche to fill, because so many people live in urban environments and/or on a very low income, and all too often they jump to the conclusion that permaculture isn’t for them, since they don’t own a farm.

Hopefully by now, the myth that you have to be a landowner to do permaculture has been dispelled! Still, some of you DO have access to big land, and there are for sure certain important factors to consider when designing on a larger scale. Even if you don’t have a farm, this article will help you recognize the important of scale and give you a bunch of inspiring examples of what can be done on large sites.

What Do We Mean by “Farmscale”?

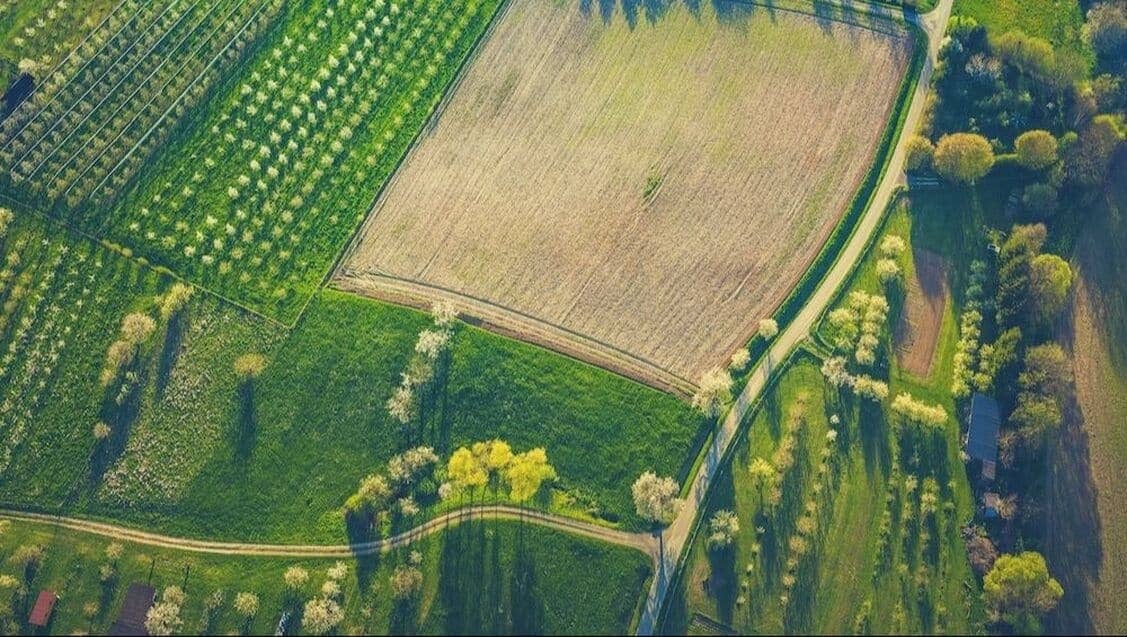

The answer to a lot of questions in permaculture is “it depends,” and this is often because of scale. We can all probably agree that 100 acres and bigger could be considered big, and that an apartment balcony or a tiny urban patio is small, but of course it’s much more complex than that. It’s not just about the size of the land, but about the scale and intensity of the projects being undertaken, the amount of people involved, the boundaries framing the design, and much more.

So, for clarity’s sake, and based on the demographics of the our student community, we are calling anything above an acre “farm scale.”

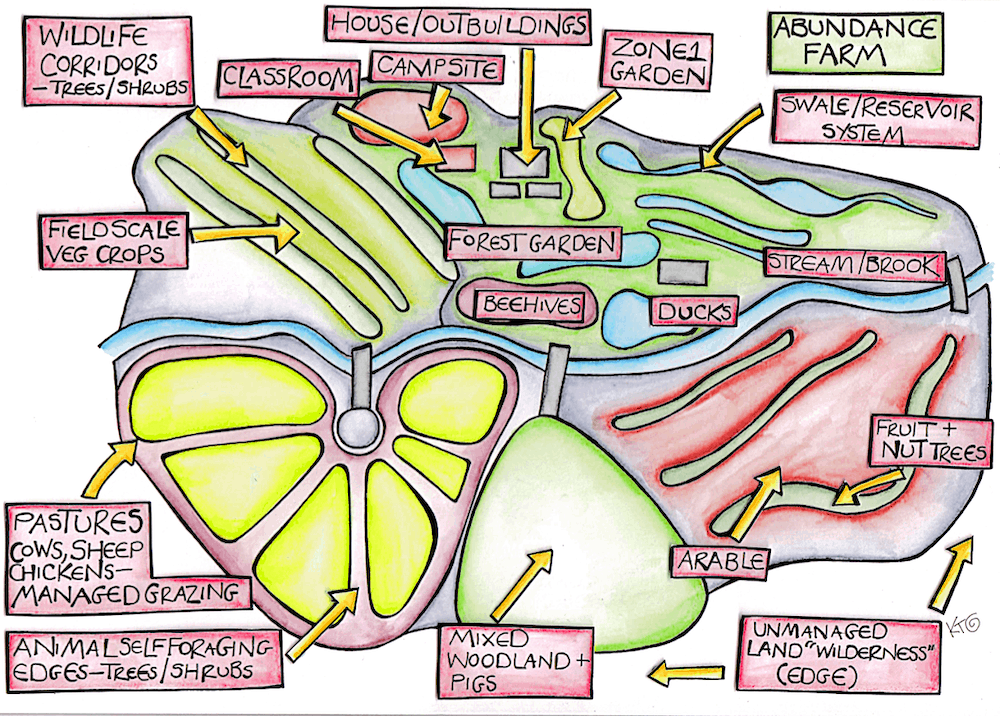

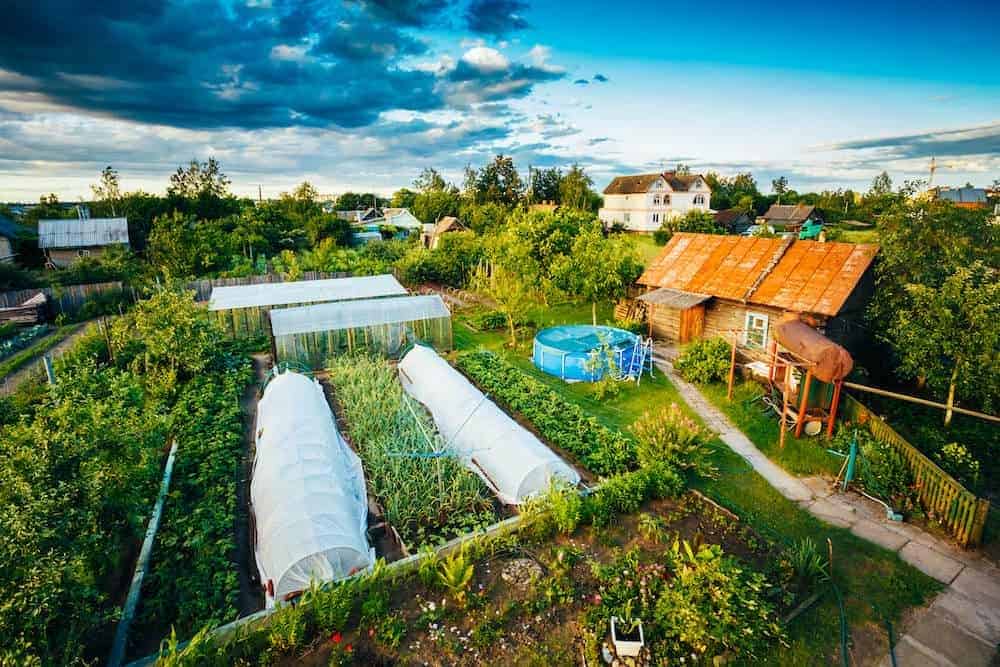

Zooming into the outer zones: the size and relative location of your zones will look quite different on large vs. small sites.

As you know, “zones” are patterns of human use, and are organized by how productive they are, how much maintenance they need, and the resources such as water, materials or energy that they require. As you remember, zone 0: your home and yourself, zone 1: the domestic zone, and zone 2: the orchard zone. Let’s look more closely at zones 3-5.

The outer zones are not all about owning lots of land. Zones are simply a tool to help you work out the best place for things in your design. They reflect how frequently you need to work in a particular part of your site, or how often you visit it, so even on a small plot you may have, or be able to create, outer zones. For example you may have a couple of logs inoculated with mushroom spores (zone 5) in amongst a food forest on what used to be your front lawn (zone 2). Alternatively, you can use the wider community, including parks, wild spaces, incubator farms, or your neighbors’ gardens for these zones.

Zones can also be used to reduce carrying heavy things further than you need to. For example, the fruit trees in the orchard zone don’t need tending every day, but when the fruit is ripe, having it near the house is a huge advantage and means the crop is more likely to be enjoyed to its full.

Zone Three

Zone 3 is typically called “the farm zone,” but this could also be (varies widely according to context):

- Your local community garden where you volunteer regularly and harvest some seasonal produce.

- A guerrilla garden that you look after whenever you are passing by.

- A bed of perennials in a corner of your garden that just needs occasional weeding.

- The fields away from the house. Livestock grazing in these fields will still need to be checked regularly, but they don’t need tending individually every day or have food or water carried out to them.

Zone Four

Generally called “the forage zone,” Zone 4 tends to be seasonal in use. This could include:

- A community woodland where you can practice woodland crafts from coppiced wood.

- The hedge out on the perimeter where you gather herbs and flowers.

- A hillside nearby where locals go to pick berries.

- Nut trees or a foraging area you nurture in a far corner of your garden.Hedges throughout the farm where you pick blackberries.

Zone 5

These are the wild areas, where you may still go but generally don’t try to change or control. This could include:

- The spider webs that you leave undisturbed in the windows or on the balcony to catch flies.

- The footpath by the canal or the cycle path along the old railway track.

- An abandoned factory or unused plot on the industrial estate where you work.

- A shady corner in a back alley where you collect mushrooms once a year.

- A pond or woodland on your land or in the park where you go to meditate and watch the birds.

Whether you own land yourself, are renting it or are managing it as part of a community group, there are significant differences to managing land on a big scale. It’s worth taking the time to think through the challenges and design a system that works for you and/or for the group.

The good news is that there are a wealth of traditional and Indigenous practices we can learn from, adapting ideas to suit current circumstances. New terms appear regularly for “new” sustainable approaches to farming but they are usually a re-packaging of traditional and Indigenous ideas and practices.

There is no such thing as a blank slate.

If you’ve recently purchased land as a “blank slate,” in a community you aren’t from, please take a moment to read this article, about Why My Farm Isn’t a Permaculture Farm.

In general, managing more land does take more time. But you can stack functions and harness flows in ways that radically reduce the inputs. For example, if you have to walk across the farm every time you need tools for the garden in your front yard, it makes more sense to have a second tool shed, close to home, than it does to spend the time walking back and forth. On a small site, this extra effort would be a negligible amount of minutes per year. But on large acreage, it could add up to several hours a year.

So the larger you get, the more you have to account for things like travel time and relative location.

Tips for Determining Appropriate Design Scale for Big Land Projects

Figure out the scope of your project.

Observing your site, determining your goals, understanding your boundaries and evaluating your resources will help you to understand what the scope of your project is. You’ll get much more familiar with these steps as you start to engage with the Design Studio.

To avoid making unnecessary investments and poor decisions, it is important to decide whether you want to make your permaculture project into a livelihood project or a hobby project. You may also wish to think about whether it will be just yourself and your family on the site, or if you will be inviting others to live, work, and contribute. This is an important distinction to make and will determine how you go about designing and investing in your site.

Consider some ideas around “going big”:

Ask not what the land can do for you, but what you can do for the land. If you have access to a large parcel of land, think about the ecological benefits of establishing big, thriving zones 4 and 5. You may consider establishing permanent wildlife corridors, rehabilitating degraded riparian zones, replanting native at risk species (with help from trained naturalists), or simply allowing nature to take its course and cultivate biodiversity and healthy soils through succession. The benefits of these decisions will be felt for miles around in the wider ecosystem.

It’s a chance to collaborate and build community. Think of the social, cultural, spiritual, experiential, and intellectual wealth that can be grown on a large parcel of land. This may happen through working with local artisans, non profit groups, Indigenous communities, schools, seniors centres, youth programs etc. The land could become a model of large-scale sustainable land management. If you own the land, then recognize that you are one of a very privileged few. It would be beneficial to think about what kind of responsibility you are willing to take on with regard to the “fair share” ethic.

You could design a livelihood in collaboration with the land. If planned and executed with care and forethought, it’s possible that you could make a sustainable livelihood through agriculture, probably coupled with other sources of income, such as running workshops and other offsite projects.

At any scale, agriculture is hard work and requires planning, energy, perseverance, and drive. Your yields might come in the form of experience, exercise (a euphemism for sore muscles), community growth, or spiritual satisfaction before they come in monetary form. It’s important to ask yourself why you wish to pursue this path.

Consider some ideas around “staying small”

Biting off more than we can chew is a common occurrence with new, over-enthusiastic permaculturists. Especially when we get access to a large property, it can be tempting to work off of vague ideas or beautiful photos in magazines, then make poor financial decisions and end up disappointed in ourselves and perhaps a little bit bitter towards the whole “permaculture thing.” Be honest with yourself and be realistic. If being realistic means not buying a large property or just focusing on designing a small garden patch in front of your house, then that is your appropriate scale.

Stay small at first. Scaling up isn’t always the best choice right off the bat. Even on a large property, you can scale down approaches like orchards, swales, and field crops and concentrate them in a small food forest garden that can be observed, learned from, and expanded at a later time if needed. In permaculture, we often use an approach called “design by chunking”. This means that we don’t need to plan the entire project in detail to begin with. We pick a small section and develop that first, before moving on with implementing other sections of our design.

Smaller scale being more efficient is backed up by a UN study. The IAASTD report on the future of world agriculture was written in response to the question: “How are we going to feed the world?” It was expected to find out that the answer was biotechnology and agro-industry, i.e. genetic engineering and industrial scale farms growing monocrops.

Instead, its main findings included:

- Women do most of the food production worldwide.

- Traditional and local knowledge is important.

- Small farms and gardens make more efficient use of the land.

- Small farms and gardens are significantly more productive than industrial scale monocrops.

Big land permaculture examples

Here is a selection of big land permaculture projects around the world. Take a few minutes to visit each website and note what about their designs call your attention, what types of crops or infrastructure are being used, and if you come up with ideas from these examples, jot them down!

This is by no means an exhaustive list of global permaculture projects. It is meant only as a sampler to show you a range of examples. As you explore, consider how everything you have learned about permaculture and design so far is different when applied to big land versus an urban or suburban site.

Spring Grove, Minnesota, USA. Woodland is the natural habitat for pigs. Having access to woodland means the pigs find most of the food they need from the wide variety of plants and grubs available. Rotational grazing means there isn’t a build up of parasites, so both the pigs and the pastures/wooded areas are healthier. The design for Nettle Farm, located in the Midwestern USA, incorporates rotational grazing for the pigs through both pasture and woodland.

Llananant Farm, Monmouthshire, Wales, UK.

The nant (stream) from the farm’s name runs through the middle of the farm. Because the stream is a permanent feature that can’t be relocated, it made sense to create zone 5 across the middle of the farm. With help from an agri-environment scheme, a swathe of land either side of the stream has been fenced off and is now a strip of woodland. The advantages are that it provides shade, shelter and browsing for livestock in the fields on both sides of the woodland. The trees include alder, a nitrogen-fixer that is particularly nutritious for browsing stock, and willow, a natural source of salicylic acid (aspirin). The woodland also provides a haven for wildlife, increases biodiversity, and helps prevent flooding.

Vergenoeg Project, Namibia. Vergenoeg, Eastern Namibia.

Anna-Marta of Permaculture Namibia’s Vergenoeg Project talks in this video about how training opportunities can empower women. Vergenoeg is a village where the San people, or Bush people, were settled because cattle farming and colonial land ownership laws have made their hunter-gatherer lifestyle impossible.

Sabina School, Uganda. Rakai, Southern Uganda.

On a 110 acre site, Sabina School accommodates 600 children from the surrounding area, where HIV/AIDS has had a devastating impact. One result is that children may not learn essential skills from their parents. To address this, and to help make the school sustainable, an ambitious permaculture design is being applied to the whole site, and part of the design is that it is integrated fully into the daily life and education of the children.

Palestinian farmers use permaculture to challenge occupation.

In this article, Sarah Irving looks at two permaculture farms in Palestine: Murad al-Khufash’s permaculture demonstration centre, which is now on his family’s farm, and Bustan Quraaqaa, founded by permaculturist Alice Grey who lived in Palestine for 10 years. The article looks at the particular challenges farmers face in Palestine and talks about how permaculture ideas and techniques can help farmers overcome these problems, at least to some extent.

Project Wadi Attir. Negev Desert, Israel.

Lina Alatawna, a young, Bedouin woman, is the Director General of this initiative of the Bedouin community in the Negev desert. The Bedouin have thousands of years of experience living sustainably in the desert, but their nomadic way of life is under threat, and they are currently a marginalized and vulnerable community. Project Wadi Attir is establishing a model of sustainable agriculture in an arid area, illustrated in this interactive map of the project’s site.

Caring for our Country: Recording Indigenous Ecological Knowledge. Northern Territory, Australia.

The Central Land Council represents Aboriginal people in Central Australia and supports them to manage their land, make the most of the opportunities it offers, and promote their rights. It emerged from the Aboriginal struggle for justice and land rights. Their Caring for our Country program is enabling people to record Indigenous Ecological Knowledge through making videos with older relatives. As well as being available in the communities, these videos are being shared with the wider world via their website.

Want to learn more about this and other topics related to permaculture, sustainability, and whole-systems design? We offer a range of FREE (donations optional) online courses!